My favourite data race demo.

This problem blew my mind way back when. Prof. Ben-Ari presented this example as a case of “parallel programming has pitfalls”. In a lecture hall of a hundred or so engineers, there was not a single correct answer…

What is the output of this program? Two threads racing to each increment a shared variable 10 times.

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

int main(void)

{

volatile int var=0;

auto worker = [&] () {

for( int i=0; i<10; i++) {

var++;

}

};

std::thread threadA = std::thread(worker);

std::thread threadB = std::thread(worker);

threadA.join();

threadB.join();

std::cout << var << std::endl;

}

20? Anything between 10 and 20? Something completely different?

Spoiler prevention - click to show answer.

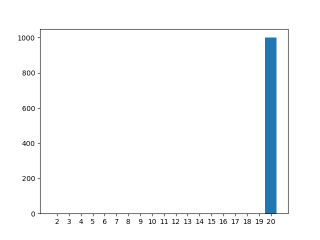

2-20. Proof that result can be less than 10 is given below, explanation is left as an excercise for the reader.The source is available here, along with a driver script and plotter. The script runs the generated binary a thousand times, and generates the figures below.

Results

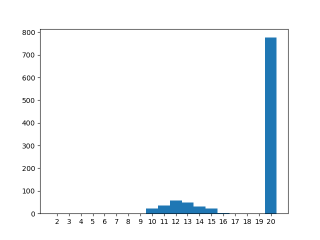

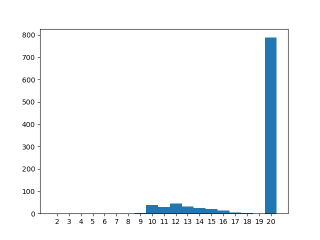

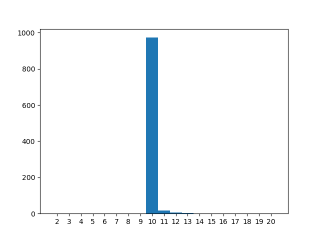

Running the above code on my laptop (Intel i5-7300 @ 2.6GHz, GCC 9.3.0, Linux 5.4). The “correct” answer is the most common one, but there is a non trivial amount of cases demonstrating the race.

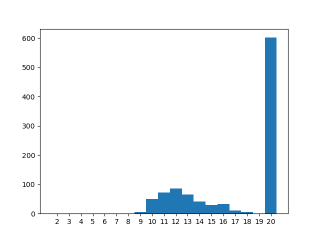

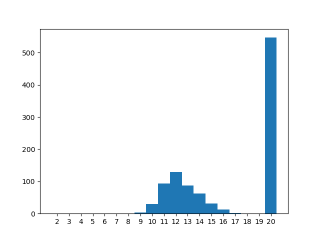

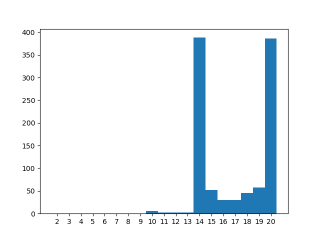

The plot changes subtly if the binary is compiled with full optimization (-O4). Seems that with a higher optimization level, threadB starts faster and is therefore more likely to cause the race.

Interestingly, on my desktop (AMD Ryzen 7 3800XT @3.6 GHz, GCC 10.3.0, Linux 5.11) the results didn’t vary over optimization level. Is this because of the compiler or the processor?

Variations

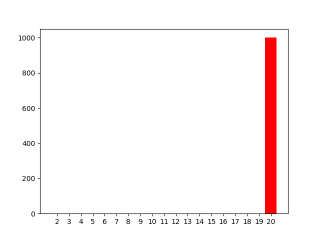

System under load

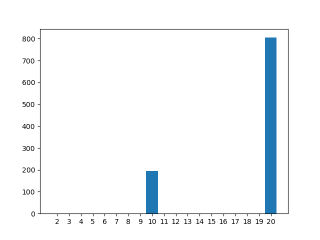

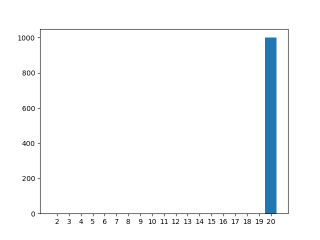

If the system is under CPU load the thread startup becomes much slower, and most of the time threadA has finished before threadB starts. At optimization level -O0

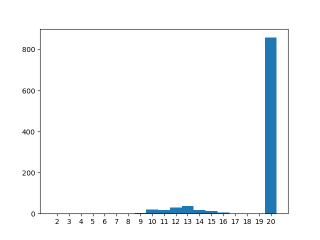

And at -O4

Not a volatile

Dropping the ‘volatile’ should change the outcome significantly, but it doesn’t. var should not now need to be read and written

back between increments, yet the result is this:

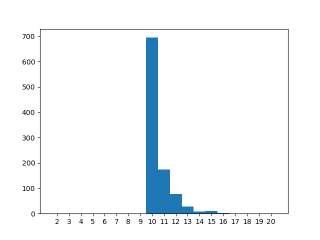

Only when also icreasing the optimization level (to -O4) does the expected result show up. Seems the compiler has managed to hoist out the load and store of ‘var’ outside of the for-loop only with high optimization. Here the race between the threads has changed to does threadB start before threadA finishes. I.e. does threadB start from 0 or 10.

Increasing the workload by sleep

Changing the worker thread’s timing a bit gives a more profound demo of the race.

auto worker = [&] () {

using namespace std::chrono_literals;

for( int i=0; i<10; i++) {

std::this_thread::sleep_for(1ms);

int tmp=var;

tmp++;

std::this_thread::sleep_for(1ms);

var=tmp;

}

};

And the same under system load:

The sleeps here synchronize the worker threads such that the sub-10 results cannot happen.

Increasing the workload by repetition

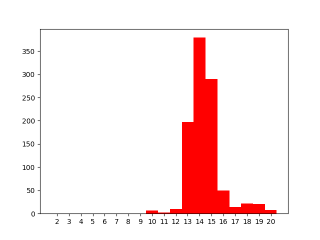

If instead of 10 increments, the worker runs 10000, the probability of hitting the race condition increases significantly. Result is divided by 1000 to get it back into same scale as other tests.

auto worker = [&] () {

using namespace std::chrono_literals;

for( int i=0; i<10000; i++) {

int tmp=var;

tmp++;

var=tmp;

}

};

...

std::cout << var/1000 << std::endl;

Now the effect is clear. Curiously 10 does appear, but sub-ten values are very rare.

On the AMD desktop the race is finally visible, but without the peak at 20 that can be seen on the laptop? This means that

- the laptop processor runs the loop faster

- the laptop is slower at starting up new threads

- something real strange is going on with cache coherence

But which? And is it because of CPU architecture, GCC version or kernel version? More in depth analysis would tell, but my guess is that the overall combination of the desktop setup means thread startup is much faster than on the laptop. This would also explain the other anomaly with the desktop above.

Synchronous start

Trying to synchronize the thread starts after thread creation like so seems to remove the race completely. Most likely due to the overhead of calling the synchronization routines.

Solution

The proper way to fix this is to change volatile int var=0; to std::atomic_int var(0);

This slows the execution down so much, that even a crude measurement of the bash script (excluding compilation and plotting) notices a 10% increase in execution time.

Home